“Design is the silent ambassador of civilization.” – Buckminster Fuller

We often praise architecture for its visible glory—gleaming towers, iconic bridges, historic facades. But beneath these celebrated structures lies another, quieter form of architecture—one that doesn’t aim to dazzle the eye, but to shape behavior, enforce policy, and sometimes exclude without a single spoken word.

This is invisible architecture—the subtle, often unnoticed elements of urban design that control, guide, or restrict how people experience the city.

1. Hostile Architecture: When Cities Say “You’re Not Welcome”

Take a moment to picture a public bench. Now imagine it has metal armrests evenly spaced across it. Comfortable for sitting—impossible for lying down.

That’s not by accident.

This is a form of hostile architecture, a growing design trend in urban environments that aims to deter behaviors considered undesirable—most often those of vulnerable populations like the unhoused, teenagers, or the mentally ill.

Other examples include:

- Spiked window ledges to prevent people from sitting.

- Sloped bus stop benches.

- Fenced-over vents that used to provide warmth in winter.

Such measures communicate a message loud and clear: This space is not for everyone.

While these features are technically part of the “design,” they reveal the troubling question: Who gets to belong in our cities?

2. Design as Silent Policy

Architectural design and urban planning are never neutral. They’re an extension of policy and power—tools that shape social dynamics as surely as laws do.

For instance:

- Redlining in the 20th century wasn’t just financial discrimination—it was spatial. It shaped where people could live, and in doing so, it shaped generations of inequality.

- Zoning laws often prohibit multi-family housing in high-income areas, quietly preserving economic segregation.

- Highways in the U.S. were often intentionally routed through Black neighborhoods, displacing communities and cutting them off from resources.

In this way, architecture becomes a quiet enforcer of privilege, influencing who can afford to live in a neighborhood, how long someone spends commuting, or even whether children have access to green space.

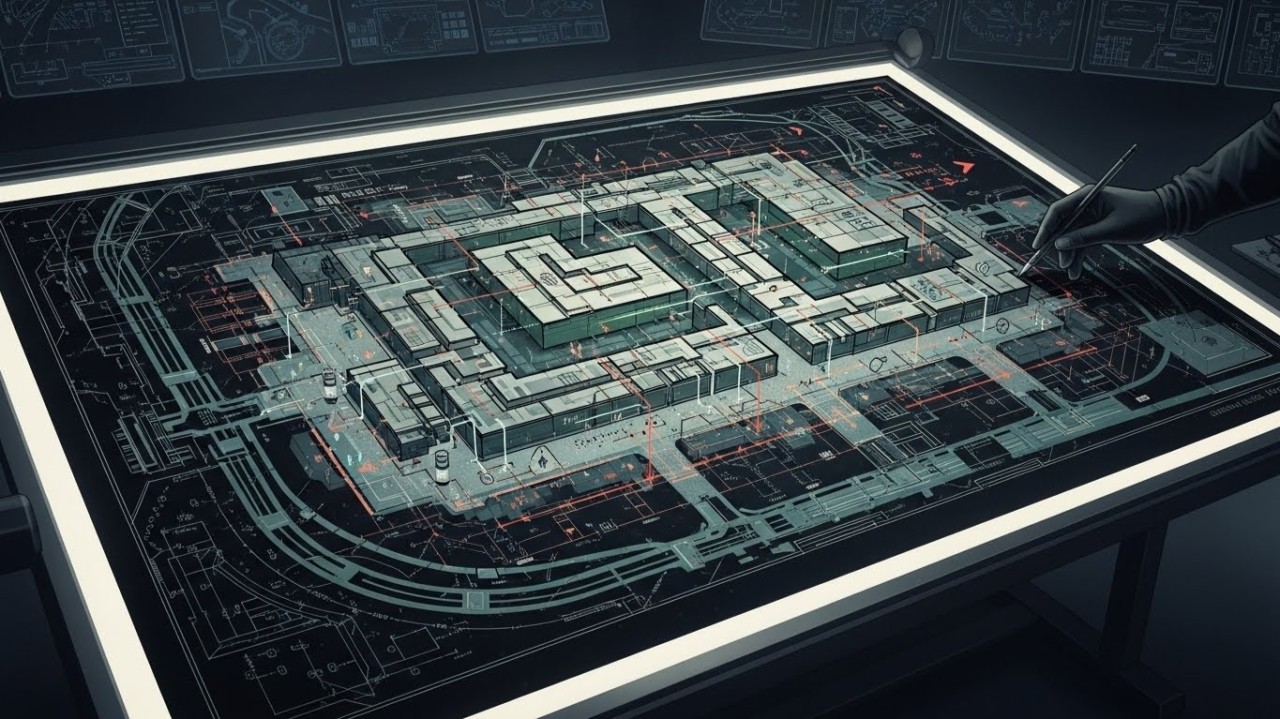

3. Surveillance by Design

The modern city isn’t just watched—it’s built to watch you.

- Open plazas in financial districts offer clear sightlines for crowd control.

- Lighting and bench placement in parks affect where people gather (or don’t).

- Entry/exit bottlenecks make mass events easier to police but harder to escape in emergencies.

Surveillance doesn’t begin with the camera—it begins with the architect’s pen.

In these spaces, architecture is not just a structure. It’s a strategy.

4. Who Gets Comfort?

Design equity becomes painfully obvious when you compare a luxury commercial zone to a transit hub in a low-income area.

One has:

- Shade trees

- Drinking fountains

- Ample seating

The other has:

- Broken pavement

- No shelter

- No place to sit

This disparity isn’t accidental—it reflects a value hierarchy embedded into the design. Comfort, rest, and dignity are too often seen as amenities, not rights.

5. Reclaiming Space: A Movement is Growing

Fortunately, a new wave of urban thinkers, designers, and everyday citizens are pushing back.

– Tactical Urbanism

Pop-up parks, temporary bike lanes, and chalk-drawn community spaces bring design back into public hands.

– Inclusive Design

From gender-neutral public restrooms to universally accessible sidewalks, equity-first thinking is reshaping cities for everyone.

– Design Activism

Grassroots groups are using design to expose inequality and reclaim space—turning overlooked areas into community gardens, art spaces, and public forums.

Invisible architecture teaches us that silence can speak volumes. A bench with a divider. A park without shade. A plaza with no exit.

Each of these is a choice. A design decision. A message.

As architects, planners, and citizens, we must learn to see the unseen. Because once we recognize invisible architecture for what it is, we can begin to redesign our cities—not just for efficiency, but for empathy.

Let’s build cities that welcome, not exclude.